Eviner contributes to NAS report on Owens Valley dust

Solution: Manage water, land use and native plants to minimize air pollution

Is dust inevitable in southeastern California’s Owens Valley? A new federal report says “no,” supported by work from Valerie Eviner, a professor in the Department of Plant Sciences.

Dust blowing into nearby communities – and the health problems it causes for people who breathe it – can be greatly reduced, the report says. Solutions include planting native plants in dust-producing areas above the largely dry lakebed, agencies and landowners working together, and including local Native American tribes in the entire process.

But work is needed to understand better what the dust is made of and where the dust comes from, the study concludes.

“A major source of controversy is where this dust is coming from and if anything can be done to control it,” said Eviner, a member of the Owens Lake Scientific Advisory Panel, created by the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine. “Or, are deserts just dusty, and poor air quality is inevitable in the Owens Valley?”

Advisory panel members released their report, “Off-Lake Sources of Airborne Dust in Owens Valley, California,” late last week.

The scientists carefully evaluated sources of dust around Owens Lake, apart from the former lake itself, where dust-control measures have seen great success. The researchers found that those off-lake areas still are responsible for significant amounts of air pollution.

“And, they are likely to become worse sources of dust due to climate change,” Eviner wrote. “While some sources of dust, like flood deposits, are natural, we expect those to create even more dust, as climate change increases the frequency of extreme wind storms and rain storms.”

Eviner is an expert on managing landscapes for ecological resilience. She contributed to the report by assessing how Owens Valley had naturally controlled dust before people diverted most of the valley’s water. She also investigated feasible steps that can restore native vegetation.

“Native plants are incredibly effective at minimizing dust, but to restore these plants, it is critical to maintain steady groundwater availability for them,” Eviner added.

Path forward: Use the tools at hand

For a century, Owens Lake in southeastern California has been largely dry, becoming the largest source of airborne dust in the United States.

Scientists involved in the study looked specifically at bits of dust that are 10 micrometers or less in diameter, called PM10. These bits are small enough that, when people breathe them, they get stuck in their lungs. Short-term exposure can worsen asthma and COPD symptoms, leading to increased emergency room trips. Long-term exposure may damage the lungs and can increase the risk of respiratory-related deaths, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Standards for dust coming off the lake are set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. But, the EPA can waive those standards for moments of extreme air pollution that are considered “natural.” Part of the controversy, then, is over what constitutes “natural.”

“Extreme floods and fires are examples of these natural events,” Eviner wrote. “While they certainly can occur naturally, human modifications of the landscape, vegetation, water flow and climate all are making these ‘natural’ events more frequent and more intense.

“In our changing environment, it is critical for regulatory agencies to reconsider what is considered natural, and to push for pre-emptive management that minimizes the frequency and impacts of these types of events,” Eviner recommended.

“In many cases, we have the ability to minimize dust emissions by enhancing native vegetation and improving water flow,” Eviner wrote, adding this is “critical” to mitigating the dust. That requires managing the use of groundwater to support those plants. But what was sufficient groundwater in the 1800s, when the valley was lush, may not be enough in the future, as climate change makes summers hotter. “The solution may require more water to be left in the valley to keep it resilient,” Eviner wrote.

Pre-emptive management includes managing the use of groundwater. The report recommends incorporating the wisdom of Native American people in the region, who have generations of tribal experience with manipulating water to benefit plants in the valley.

From “land of flowing waters” to dust bowl

The report is the latest in a storied and highly litigated history of the lake and valley, and their fraught relationship with the thirsty and growing behemoth 220 miles to the southwest.

Native people called it “Payahuunadü,” meaning “land of flowing water.” It was full of swampy lowlands supporting prolific plant growth. Tribes maintained irrigation canals that fostered abundant agriculture of native plants throughout the valley, Eviner wrote.

By the late 1800s, farming by white settlers in Owens Valley reduced water in the lake. In 1913, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power opened an aqueduct to divert water to the growing city, reducing the lake even more. The diversion also prompted decades of lawsuits and even a dynamite attack on the project in 1924, plus a Hollywood movie dramatizing the intrigue.

In the 1970s to 1980s, extensive groundwater pumping in Owens Valley also decreased the extent of groundwater-dependent natural vegetation north of the lake. The lake became one of the largest sources of airborne particulate matter in the U.S., the report states. Meanwhile, the greater Los Angeles metropolitan area continued to boom; now it is home to about 13 million people, the second-largest metro area in the country, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The National Academies of Sciences was asked to establish the advisory panel after a 2014 legal settlement between the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District, which oversees air quality throughout Owens Valley, and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. Scientists on the panel, including Eviner, are offering ways to control dust from the dry lake bed and, with this latest report, from areas surrounding the lake bed.

Also as a result of that 2014 settlement, the L.A. water department is now financing the largest dust control project in the nation, covering nearly 49 square miles of the lake bed. Those efforts have reduced airborne dust by 99.4 percent, according to the district.

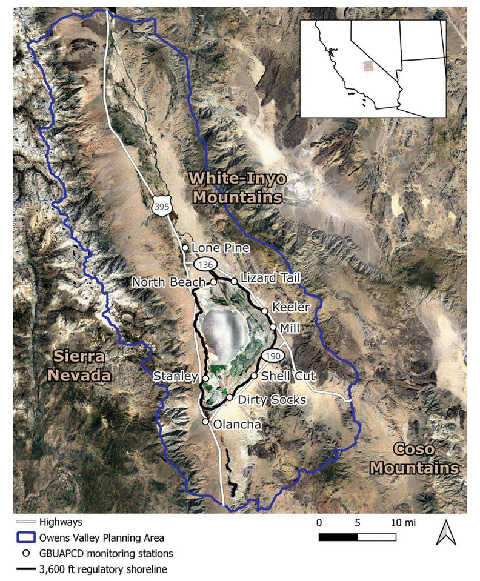

From 2017 to 2024, however, significant airborne dust continued, especially when high winds blow. Flood areas above the lake bed are the biggest sources, the NAS report states. Other major sources are Olancha Dunes and Keeler Dunes. Olancha Dunes is home to the federally operated Olancha Dunes Off-Highway Vehicle Area. Keeler Dunes historically was vegetated and emitted little dust. “The decline of vegetation on Keeler Dunes is at least partially due to dust from Owens Lake sandblasting the vegetation,” Eviner wrote.

Highway infrastructure adds to the problem, the report states. Area highways divert rainwater, creating sheets of sand that easily can become airborne.

All these areas are likely to continue causing dust in the future, the NAS panel warns.

Solutions are available, but Eviner cautioned: “Maintaining healthy air quality depends on policy that dictates whether we use the tools we have.”

Read the report

The Owens Lake Scientific Advisory Panel’s report, “Off-Lake Sources of Airborne Dust in Owens Valley, California,” is free and can be downloaded here.

From 2019 to 2020, Eviner served on an earlier NAS panel concerned with dust coming off Owens Lake. That panel’s report is here.

Media Resources

- Trina Kleist, UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences, tkleist@ucdavis.edu, (530) 754-6148 or (530) 601-6846.