A ‘thirsty nightshade’ could give tomatoes salt, drought tolerance

New breeding lines developed by UC Davis’ Rick Center

New lines of tomatoes are being made available for research, and they carry the pluck of a desert-dwelling distant cousin that could make future crops better able to thrive in heat and drought.

It marks the first time that genes from Solanum sitiens have been introduced into cultivated tomato lines that are readily accessible to scientists and breeders. Its name is Latin for “thirsty nightshade,” and it blooms in one of the world’s driest places, the Atacama Desert of Chile. Accustomed to little water, chilly temperatures and salty soil, the wild plant has been bred with market tomatoes. Researchers hope the resulting 56 new lines may contain the qualities of both: grocery store beauties that shoppers would love, plus traits that could help farmers in California and beyond as climate change makes it harder to grow the state’s $1.5-billion crop.

“Now the work starts to see what traits these lines carry,” said geneticist Roger Chetelat, director of the C.M. Rick Tomato Genetics Resource Center, based at the University of California, Davis. “This is just the beginning.”

The goal of Chetelat’s team was to create a permanent genetic resource for tomato researchers and breeders. Among its desert qualities, seeds of this “thirsty nightshade” sleep in the soil for years until a good rain comes. This trait could provide clues to how seeds regulate germination in response to environmental cues. In addition, its fruit ripens much more slowly than market tomatoes and never softens, so it likely carries genes for fruit firmness. These and other characteristics could be explored through these new lines to, eventually, develop tomatoes that would thrive in the future.

“We transferred as much of the genome of S. sitiens as we could, about 93 percent,” said Chetelat, who is based in the UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences. “Rather than work on just one problem, like drought stress, we wanted to transfer the whole genome so it could be used in the future for various traits of interest.”

Tomatoes like the ones we enjoy in our salads could not be grown in many agricultural areas without the addition of genes from wild relatives, which contribute qualities such as disease resistance, Chetelat added. The new breeding lines are the latest result of decades of seed collection and genetic research at the Rick Center. Researchers and breeders who are interested in getting seeds or learning more about this resource can visit the TGRC website.

Hardy tomato relative in danger of extinction

Solanum sitiens grows on barren, arid slopes of the Andes in South America. In some areas, it is the only plant that thrives.

A UC Davis scientist, Charles M. Rick, started collecting the seeds of tomatoes and its wild relatives in the nightshade family in 1949 and continued for decades. More recently, Chetelat, his students and collaborators from Chile searched remote areas in that country to find new populations of S. sitiens and other wild tomatoes.

The region is rich in copper ore, and intensive mining activities threaten the few areas where the plant is known to grow. Chetelat and collaborators worked with the Chilean government to have S. sitiens listed as an endangered species.

A similar situation exists in neighboring Peru, where many of the plant populations that Rick and others collected previously have since disappeared. “We go back to historic collection sites, and we see it’s now a sugar cane field or a shopping mall,” Chetelat said. “The wild tomato populations have mostly disappeared from the agricultural valleys. At higher elevations, you still see more small-scale agriculture, so those populations still survive.”

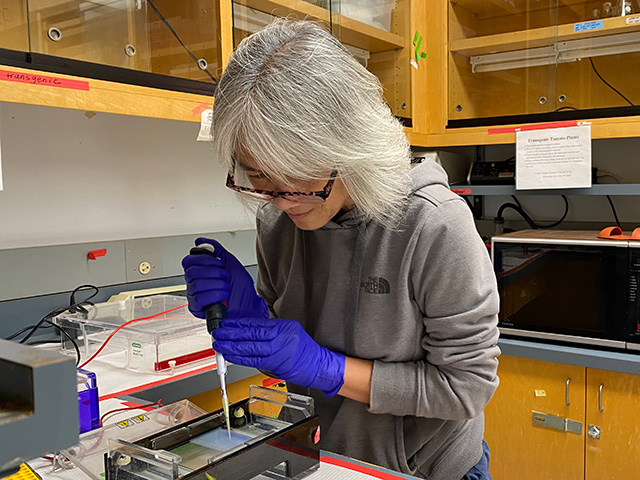

Back in Davis, Chetelat and team strive to keep their rich seed collections viable. Growing the “thirsty nightshade” and other wild tomato kin in a greenhouse is challenging, but ensures their genetic treasures can be studied in the future.

“We don’t want to see these plants be eliminated in the wild,” Chetelat warned. “If we want tomatoes in our salad in the future, we need to protect the wild places where these plants come from.”

More about “thirsty nightshade” and the Rick Center

Learn more about the C.M. Rick Tomato Genetics Resource Center here.

In 2019, Chetelat and team published a paper about their work with S. sitiens and explained the foundation of the new breeding lines: “Introgression lines of Solanum sitiens, a wild nightshade of the Atacama Desert, in the genome of cultivated tomato.” Roger T. Chetelat, Xiaoqiong Qin, et al.

Former graduate student Carl Jones recounted the challenges and excitement of collecting wild tomatoes in northern Chile in this 2005 article published by In Good Tilth: “The extreme search for tomato genetics.”

Media Resources

- Trina Kleist, UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences, tkleist@ucdavis.edu, (530) 754-6148 or (530) 601-6846