Hosseini, Fatino offer parasite management strategies

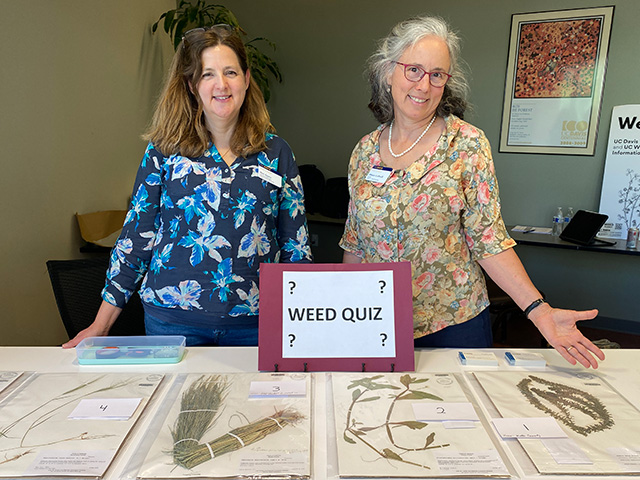

Weed Day includes Orobanche research

It makes pretty little lavender flowers with sweet yellow centers, but broomrape is a crop-crashing parasite whose seeds can last for decades in the soil. Research on how to control the plant, in the Orobanche family, was among the topics covered at the recent UC Davis Weed Day.

In addition to lurking in the soil, broomrape seeds are small and disperse easily. The parasite is posing huge challenges to California’s processing tomato industry, which is tops in the nation and worth $1.2 billion in 2022, according to the state Department of Food and Agriculture. Worse, Orobanche could spread to other vegetable crops.

“Integrated weed management is the way to go,” advised scientist Pershang Hosseini. That means a variety of strategies, including savvy cultivation practices, physical removal, biological approaches and the use of herbicides as a supplement.

Hosseini is a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Brad Hanson, a professor of Cooperative Extension in the Department of Plant Sciences and co-organizer of the event.

Hosseini: Catch and trap

In one avenue of research, Hosseini is looking at using trap crops and catch crops to draw down the number of seeds in the soil.

Orobanche seeds wait for chemical signals coming from plants they like to latch onto, such as tomatoes. When a seed detects that signal from the root of a potential host, it sprouts, then attaches to the host and sucks away water and nutrients. Trap crops, such as chili peppers and some kinds of beans, produce that enticing chemical signal, stimulating the Orobanche seed to sprout. But trap crops have other qualities that prevent Orobanche from attaching to their roots. Unable to attach to a host, the young free-loader dies.

Catch crops use a different bait-based approach: Catch crops, such as lettuce, also stimulate Orobanche seeds to sprout, and in this case, the parasite attaches to the host plant. Growers wait until the parasite is established, then harvest or destroy the host crop before the parasite can make more seeds. Again, seeds banked in the soil are used, but don’t lead to Orobanche plants that can reproduce.

Heat plus flood, humidity equals nearly zero sprouts

In another avenue of research, Hosseini is investigating the use of flooding combined with heat to neutralize Orobanche seeds. “We’ve had reports of growers seeing no emergence of broomrape in fields after being rotated with rice,” which typically are flooded, Hosseini said.

With the help of undergraduate Plant Science student interns, she has been conducting experiments in the lab to simulate flooding of seeds under temperatures similar to those in the Central Valley during summer and winter.

Early results show that flooding under warm conditions — when soil temperatures are around 82 degrees Fahrenheit — can reduce the germination of broomrape seeds to nearly zero after four weeks. In contrast, colder conditions were less effective, Hosseini found.

“This suggests that high temperatures may make flooding more effective at reducing the ability of broomrape seeds to germinate,” Hosseini said.

In yet another experiment, Hosseini and team further explored the role of heat, this time adding humidity to the mix, to see how that combination affects the ability of Orobanche to sprout. The experiment was designed to simulate field conditions in which people hand-weed broomrape plants, seal them in plastic bags and place the bags in the sun. (This is done so that, when the bags are disposed of, Orobanche seeds are not spread to a new location.)

Hosseini’s goal was to see whether the combination of high temperature and humidity —generated by the plant material inside the bags — could dampen the germination of broomrape seeds. In the lab, the team incubated Orobanche-stuffed bags at a control temperature of 77 degrees Fahrenheit for six hours; about 90 percent of the seeds germinated. As the heat climbed to 140 degrees, that rate dropped to nearly zero, Hosseini reported.

In next steps, Hosseini will move from lab to field, putting the bags with plant material out in the sun.

“Research is ongoing to evaluate whether such high temperature conditions can realistically be achieved and sustained in the field,” Hosseini wrote.

Fatino: Herbicide, delayed planting and grafting

Matt Fatino, who also did his doctoral work in the Hanson lab, reported on field tests of two management strategies and greenhouse experiments exploring a third.

“It’s really exciting to see the grower-scale tests,” which saw Orobanche emergence reduced by 85 percent with no impact on fruit yield, Fatino told the Weed Day crowd.

One strategy was putting the herbicide rimsulfuron in irrigation water that was used on tomatoes on a large field in Yolo County, heart of the state’s processing tomato industry. A three-stage treatment of the herbicide is registered with the state for use in branched broomrape in processing tomatoes, Fatino wrote.

Tomatoes typically are transplanted into a field as seedlings. So, another study looked at timing those plantings at different stages in the season ‒ in April, May and June. The April transplants suffered a lot of Orobanche, but May saw significantly less and June almost none, Fatino reported. He suggested “transplanting infested or high-risk fields as late as feasible in the planting window is an IPM approach that we can recommend now.”

Meanwhile, scientists at UC Davis and elsewhere also are searching for resistant varieties of processing tomatoes, but haven’t found anything yet. The broomrape-susceptibility gene is really hard to remove without reducing yield,” Fatino explained.

Researchers also been looking at grafting seedlings onto rootstocks, Fatino reported. So far, grafted plants still are being colonized, but they may be seeing less colonization than ungrafted plants.

“This work being conducted with industry partners is ongoing,” Fatino wrote.

Fatino did some of the work as a postdoctoral researcher with Hanson. He is now a UC Cooperative Extension advisor in San Diego County.

Related links

Read more about research at the Hanson lab into Orobanche here.

Media Resources

- Trina Kleist, UC Davis Department of Plant Sciences, tkleist@ucdavis.edu, (530) 754-6148 or (530) 601-6846.